So, my three elements are a space station, a skipping rope and a butterfly hunter. Three seemingly incongruous elements, so this'll be interesting.

Space Station

I'm seeing three major 'types' of space station for use in this;

- Residential space station

- Research space station

- Military space station

Which one I choose will largely depend on the story, but my personal tastes (which will be overridden if they conflict with the story) lean towards the military station because military sci-fi is best sci-fi.

Skipping Rope

The most awkward element, this one will probably be used as some indicator of the presence of children. Alternately, it could be a fitness skipping rope, or even an 'accidental' skipping rope, i.e. something that must be repeatedly jumped over but isn't actually a skipping rope.

Butterfly Hunter

This is what interests me the most, because the concept of a butterfly hunter is so vast. The 'hunter' element is simple - it simply refers to someone seeking something. However, the butterfly bit is what's so interesting.

Butterfly as literal butterfly

The literal butterfly is the most obvious route - a small winged insect. Perhaps it's from the station's agriculture department as a pollinator, because nobody wants to pollinate plants by hand with a toothbrush, or a strange specimen from a distant world that catches the eye of an entomologist.

Butterfly as monster/threat

The monstrous butterfly is another fairly obvious option - think Alien meets Perdido Street Station. One idea I'm toying with is a butterfly-esque monster that is the physical embodiment of despair, driving people to suicide by its mere presence. The skipping rope would become a noose, and the butterfly's effects could be used to explore the hunter's psyche.

Butterfly as MacGuffin

The hunter needs that butterfly, and they need it fast. Perhaps it's been genetically engineered to produce an enzyme crucial to medicine, or maybe it's a priceless, one-of-a-kind specimen. Whatever it is, it's got out of containment and a wild butterfly hunt begins.

Butterfly as symbol

Butterflies are powerful symbols - of innocent childhood days spent chasing them, of personal transformation, of hope, of rebirth. The hunter could be seeking what the butterfly represents, not the butterfly itself - sort of like the blue bird of happiness from K-Pax.

Monday, 30 January 2012

Thursday, 26 January 2012

Maya - Blood Vessel

I spent far longer than is reasonable composing those blood cells, and I'm still not sure I'm happy with it.

Maya - Book

Couldn't figure out how to turn the blooming page so I turned the camera instead, and I somehow lost the table texture, but otherwise it's all good.

Friday, 20 January 2012

David Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986)

Fig. 1. Blue Velvet poster.

Blue Velvet, like so many horror stories, looks at what lurks just beneath the apparently idyllic American suburbia. Opening with picture-perfect shots of life in a small town named Lumberton, the film is very open in suggesting that this is too good to be true, starting with a gentleman watering his lawn then collapsing from a stroke. Of particular interest in this scene is that the hose becomes twisted and ceases to flow properly just beforehand, providing a very subtle piece of foreshadowing as it mirrors the obstructed blood flow in the brain that causes strokes. Following this, the camera pans down to show a plethora of beetles crawling through the grass, suggesting something unsavoury just below the surface. “The message is clear – perfection often hides deeply-rooted rot. Dreams can easily turn into nightmares. Corruption is everywhere, even in places that seem immune to it.” (Berardinelli, 2002).

The protagonists Sandy and Jeff represent the girl- and boy-next-door types one associates with light-hearted teen movies of the era, setting up an expectation that is sharply thrown aside. After visiting his father (the stroke victim) in hospital, Jeff finds a severed ear on the ground. He takes it to the police, but is more curious than the police are willing to let him be. With Sandy, the daughter of the detective in whom Jeff confides, he begins investigating himself. “What they witness is something that their mom and apple pie family life has never prepared them for” (Russell, 2001), and as the socially-enforced blinkers come off the story becomes steadily darker.

Fig. 2. Jeff and Dorothy still.

Jeff and Sandy discover that one Dorothy, a lounge singer, is being used as a sex slave by one Frank, who is keeping her son captive. Frank is, without a doubt, a complete monster. Impulsive, aggressive and without a single redeeming trait, he abuses and belittles Dorothy to the point that, when Jeff meets her, she is thoroughly broken and hyper-sexualised. This is in stark contrast to Sandy, who is the wholesome, demure young lady to Dorothy’s co-dependent masochist.

The erotic element of Blue Velvet is well-remembered, but not for any actual eroticism. The film deconstructs the concept of voyeurism, and the viewer feels utterly filthy as Jeff observes Frank’s violations of Dorothy. Jeff’s resulting sexual confusion – the sexually available Dorothy or the emotionally stable Sandy? – seems to be a direct result of his upbringing. He is completely unable to process what is happening due to his lack of sexual knowledge or experience, and as a result makes potentially life-destroying decisions. The overarching mystery plot, in which Jeff is party to mysterious revelations about the nature of the world around him, seems deliberately similar to his sexual awakening.

Fig. 3. Opening/ending shot.

In the closing scene, the town of Lumberton appears to be back to normal – all is light and sweetness, Jeff’s and Sandy’s relationship has somehow survived the ordeal intact, and Dorothy is happily reunited with her son. As with the opening, there is the constant sense that all this is too good to be true, and once again we are only seeing suburbia’s façade.

Illustration List

Lynch, D. Fig. 1. Blue Velvet poster. http://media.onsugar.com/files/2011/01/03/1/1331/13311615/01/blue-velvet-poster-c10080070.jpeg (Accessed on: 20/01/2012)

Lynch, D. Fig. 2. Jeff and Dorothy still. https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjI1oXPw9FUsWiODpB3JmeMcLJ-FVbkE-LgElQkSIRIbvT9x2-GZUa_MPtAqf-letjzNLsbLjwACyCI5zHy4G5EUwp6UOjvotE9xx-n3nDv_2fP3il0fEw-8BhFH5Gc4nR_VRqUOZoqOUSV/s1600/blue_velvet_1986_reference1.jpg (Accessed on: 20/01/2012)

Lynch, D. Fig. 3. Opening/ending still. http://www.bleedingcool.com/wp-content/uploads//2011/01/blue-velvet-570x250.jpg?d9c344 (Accessed on: 20/01/2012)

Bibliography

Berardinelli, J. (2002). Reelviews.net. http://www.reelviews.net/movies/b/blue_velvet.html (Accessed on: 20/01/2012)

Russell, J. (2001). BBC Movies. http://www.bbc.co.uk/films/2001/12/05/blue_velvet_1986_review.shtml (Accessed on: 20/01/2012)

Robin Hardy's The Wicker Man (1973)

Fig. 1. The Wicker Man poster.

The Wicker Man is, as well as a horror film and a police procedural, a study in Western attitudes to indigenous religions, and perhaps an unintentional one. Christian policeman Neil Howie is called to Summerisle, an apple-growing island off the coast of Scotland in response to a child being reported missing. When all the natives of the island deny knowledge of the child, including the child’s alleged family, Howie is drawn into a web of intrigue.

Crop failure and fertility rites are a driving force of the movie – the natives of Summerisle seek to placate an apparently angry god of the fields when their apples fail, and need a pure, virgin sacrifice with the authority of a king to give their life of their own free will. Howie is chosen as the sacrifice, and is driven into the trap through a convoluted May Day festival.

Fig. 2. Summerisle fertility ritual.

What is particularly interesting about The Wicker Man is what it reveals about Western conceptions of paganism; the film takes an unashamedly Christian-centric worldview, presenting paganism as base, perverted and a vile mockery of Christian values. Churches are defiled, sexuality is worshipped, and it appears that along with the May Day celebration, the only things the writers knew about Celtic paganism was that they performed sacrifices, valued fertility and were big on trees. While it is possible that the egregious mockery of Celtic lore is deliberately played up to make Howie uneasy, it nevertheless sticks in the craw.

It could be argued that the film ultimately presents Howie’s strict Christianity as his downfall – his insistence on remaining a virgin is what gets him killed, after all. However, the film seems to paint him as a martyr, a victim of the debased heathens. Combined with Howie’s unrelenting honesty compared to the residents of Summerisle’s deceit, there is no doubt that Howie is the moral victor. “Unlike most films about witches, this one does not suggest that somewhere a genuine Satan is manipulating events” (Honeybone, 2010), but it nevertheless seems to suggest that paganism, at least in the way it is portrayed, is immoral.

Fig. 3. The wicker man.

However, the film does present one final twist; as Howie is dragged to the Wicker Man, he tells Lord Summerisle that if his death does not bring back the apples, the people will turn to make their Lord their sacrifice. Lord Summerisle hesitates a moment, as though he is suddenly hit by the consequences of his theocracy, but then insists that the crops will not fail. This could be interpreted as Lord Summerisle not actually believing the religion he uses to maintain his authority, and that perhaps religion in and of itself is simply a means of control by authorities. “The two worldviews stand face to face, both unmasked, and in the end nothing is resolved.” (Greydanus, unknown)

Illustration List

Hardy, R. (1973).Fig. 1. The Wicker Man poster. http://alternativechronicle.files.wordpress.com/2010/10/the-wicker-man-poster.png?w=497 (Accessed on: 20/01/2012)

Hardy, R. (1973).Fig. 2. Summerisle fertility ritual. http://www.2uptop.com/sites/www.2uptop.com/uploads/images/Article%20Pics/fav_things/wickerman_1.jpg (Accessed on: 20/01/2012)

Hardy, R. (1973).Fig. 3. The wicker man. https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhfP36PkgjUoCu5Etise39mFlP5SxcS0jWTuYG6cRobNU2q3EzJ_pm4pU9uiIFTcETN2OPlkKNd0IAkdtOy9KvViwxTKHD-eHmZ54Vb8HS3agov-lyMSGwpruNJnr6EEjioZoY_zRltWWs/s1600/Wicker+Man+01.jpg (Accessed on: 20/01/2012)

Bibliography

Honeybone, N. (2010). Horror-news.net. http://horrornews.net/12602/film-review-the-wicker-man-1973/ (Accessed on: 20/01/2012)

Greydanus, S. (unknown). Decent Films Guide. http://www.decentfilms.com/reviews/wickerman1973 (Accessed on: 20/01/2012)

(Aside: apparently some people think this film is morally ambiguous. Apparently some people missed the part where Howie was burnt alive.)

Thursday, 19 January 2012

Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980)

Fig. 1. The Shining poster.

The Shining is an adaptation of the Stephen King novel of the same name, in which a family moves into an empty hotel to look after it over the winter. The father, Jack, begins to go mad, either from ‘cabin fever’ or supernatural interference – it is never outright stated which it is, and “the sense of mystery which Kubrick evokes comes in part from his failure to explain exactly what is going on, this allows people to interpret the film in different ways.” (Hill, unknown).

The hotel is visually uncanny – patterns and layouts are repeated constantly, robbing the viewer of visual cues as to location. The building is also somewhat nonsensical – the office of the hotel manager is clearly in the middle of the building, and yet inside there is a window overlooking the grounds. This subtle impossibility sets up the hotel as a place of madness, and implies that perhaps the hotel itself is its source.

Fig. 2. Jack's trustworthy eyebrows.

The hotel also hosts exceedingly tight corridors, creating heavily vertical shot compositions that create a sense of claustrophobia, even in the sprawling hotel. Add to this the fact that, once the snows arrive, the hotel is completely cut off from the rest of the world, and the building feels less like a retreat and more like a prison.

Despite this, the film is surprisingly well-lit. The snow in particular means that, even at night, the bounced light illuminates the scene sufficiently, to the point of feeling ‘wrong’. The snow places light where shadows should be, which, combined with the inherently eerie lighting from below in the climactic chase scene, creates a visual unease.

Fig. 3. Jack peering through door.

Regarding the plot, “Mr. Kubrick tries simultaneously to unfold a story of the occult and a family drama.” (Maslin, 1980). Perhaps it is a ghost story, perhaps an allegory for domestic abuse and the strains of running a household. Both elements resonate throughout the film, with the seeds of Jack’s madness apparently sown long before his arrival at the Overlook.

Illustration List

Kubrick, S. (1980). Fig. 1. The Shining poster. http://cache2.allpostersimages.com/p/LRG/22/2268/RNSZD00Z/posters/the-shining.jpg (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

Kubrick, S. (1980). Fig. 2. Jack's trustworthy eyebrows. https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgnadV_aJ9oDRCk2NEIBXdIgG-D6ewXIRCpRsjRabsJmpP_AhnF5BaKoPUgonRHJOoaDWS4TkI-HSsI4uVpYR_RjcOTFfvrDXJr9SEYA5FDxi_Iz8x1uIEoqWjydf_l8ZcC4vL7uEuJS0s/s1600/Shining+11.png (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

Kubrick, S. (1980). Fig. 3. Jack peering through door. http://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Books/Pix/pictures/2009/01/07/shining460.gif (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

Bibliography

Hill, S. (unknown). Celluloid Dreams. http://www.celluloiddreams.co.uk/theshining.html (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

Maslin, J. (1980). The New York Times. http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=EE05E7DF1738E270BC4B51DFB366838B699EDE (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

Dario Argento's Suspiria (1980)

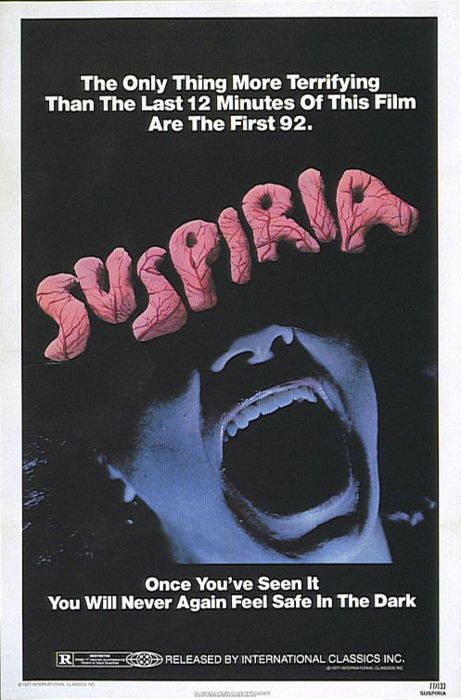

Fig. 1. Suspiria poster.

Suspiria is what going mad feels like – all semblance of reality is thrown by the wayside and left for the crows – it has a “cavalier disregard for making rational sense” (Jameson, 2011). Its use of psychedelic colour, an unrelenting soundtrack and bizarre lighting make it feel like an inescapable fever dream. The film uses stark, solid colour panels of light that serve less to illuminate as to silhouette scenes, and when they are used for illumination the bright colours make the figures and scenes seem inherently unnatural.

One can never tell what is ‘real’ within the context of the film and what is just production design. Is the ballet academy, in which the film is set, really lit so maddeningly, or is it just a figment of the protagonist’s – or the director’s – imagination? The plot is fairly simple and linear, but the film provides an atmosphere that makes it terrifying (and yet when the atmosphere passes so does the scariness, which makes it easier for a certain paranoid reviewer to sleep at night). While some ‘standard’ horror elements, such as mutilated corpses, allusions to cannibalism and relentless pursuers, are used, it is the atmosphere that makes the film truly unsettling, “a Goya print come to life relying solely on visual and audio mastery rather than plot or pacing.” (Breese, 2005).

Fig. 2. Interior long shot.

The film’s use of lighting may seem contradictory at first; the light-panels are incredibly bright, but are used to create deep black shadows. These shadows are then used to create a feeling of being surrounded, particularly obvious in the scene in which the guide dog of the academy’s former pianist is possessed and kills and eats his master. The two figures, alone, are spotlit, but completely surrounded by impenetrable shadow.

The fierce lighting creates stark silhouettes, as though the entire story is a shadow play. The improbable visuals make the film seem bizarre, and add to the sense that supernatural forces are at play. The silhouettes create an eerie stained glass effect, furthering the impression that what is happening is not natural. This, combined with the heavily geometric shapes of the film’s Art Deco aesthetic, make it abundantly clear that all is not well.

Fig. 3. Suzy mid-shot.

Notably, the bizarre visuals are limited to the academy and places where the academy has influence, e.g. the home of first murder victim. Outside the academy’s sphere, the visuals are naturalistic and sane, providing both a visual language for the witchcraft of the academy and a welcome reprieve for the viewer.

The film is rather blatant in its misogyny; women are hunted and mutilated for nothing more than the camera’s amusement, treated less like characters and more like fetish objects. This appears to be a directorial attitude, as Argento is reported by Empire as having said “A woman in peril is emotionally affecting. A man simply isn’t.” (Argento, 1997, quoted by Smith, unknown).

Illustration List

Argento. D. (1980) Fig. 1. Suspiria poster. http://media.tumblr.com/tumblr_lj9cj8PI9h1qaenv0.jpg (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

Argento. D. (1980) Fig. 2. Interior long shot. https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiSfk870Qd8PQk4ikSfpHhw5s6LQrbybNfRyR0EUlzHkxRzGyF97jqG0ko-TQAj-ihs6OW190HkV6AjdjhnpctqmSozQ8Xm5i5_TeQD4lqmXeQQehz-bw7uQnAAIbC_hW4HoZyfLr2E6Lg/s1600/suspiria2.jpg (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

Argento. D. (1980) Fig. 3. Suzy mid-shot. https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjxbaB1wK5Ld_WjTQzS3qPehx2ZvfN3CLPXjtArIvB_cbfHogb7D91y8GxMdMwIYpg1GizvoPBuLdy8vFVhhmnIQF8l8JCxEMPz0fncQpI5zPfJnARXDtqx5uCUmVDIeJWOKAYFnniNnz0-/s1600/suspiria7small.jpg (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

Bibliography

Jameson, R. (2011). Parallax View. http://parallax-view.org/2011/01/12/review-suspiria/ (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

Breese, K. (2005). Filmcritic.com http://www.filmcritic.com/reviews/1977/suspiria/ (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

Smith, A. (unknown) Empire Magazine. http://www.empireonline.com/reviews/reviewcomplete.asp?FID=132659 (Accessed on: 19/01/2012)

(As an aside, I would like to point out that this film's tagline 'you willl never again feel safe in the dark' is entirely misleading. The darkness doesn't frighten me; it's when the lights suddenly become huge solid panels of primary colours that I'll start panicking.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)