Looking at the orthopedic implications of being fused with an animal with a skeleton made entirely of cartilage - as the bones converted to cartilage, any sort of structural stability would go out the window.

Looking at combining human and shark skulls - both a shark's jaws are disconnected from the skull, allowing them to push them outwards and giving them a wider bite. In the 2/4 body sketch in the corner I incorporatede the 'lateral line', an organ of sorts on sharks that is very sensitive to vibrations in the water. Not much use on land, but neither are cartiliginous bones.

Just a quick sketch of a shark skeleton to get a feel for it. Apologies for the ink on the next page showing through, not much I can do about that.

And some Photoshop doodles. I'm struggling with silhouettes as it's not something I've tried before. Also more skeletal studies, and I learnt that sharks have their brains in front of their eyes. With a human-sized brain this has the potential to be very awkward indeed, so I migrated the brain forward to see how it looks. I'm not certain, but I'll hang onto the idea for now to see if it goes anywhere.

I also deliberately kept my glasses on all the facial sketches - I want to show that yes, even as my entire bodyt collapses I am still me, and small props like those help with that.

Thursday 29 September 2011

Tuesday 27 September 2011

Jean Cocteau’s ‘La Belle et la Bête’ (1946)

A retelling of the classic story ‘Beauty and the Beast’, Cocteau tells the story of Belle, a young woman trapped in the magical castle of a prince transformed into a monster. The story’s most obvious theme is that of not judging books by their covers, but there may be others lying underneath, perhaps not all considered consciously by the creators.

Fig. 1. Belle and the Beast still.

Belle comes to develop sympathy and even pity for the Beast, likely due to his chivalric nature that is clearly in conflict with the instincts of a predator. However, from a 21st century perspective it could be argued that Belle is showing signs of Stockholm syndrome, a condition in which the victim of a kidnapping becomes emotionally dependent on their kidnapper. While indeed the Beast is deserving of sympathy, and provided Belle with riches beyond her wildest dreams, he still locked her in a gilded cage and engaged in emotional blackmail when he said that he would die of grief if she did not return.

However, it must be remembered that in 1946 such behaviour was considered romantic rather than manipulative. At the time the Beast’s devotion was the height of chivalry, and was used, like in the Fly movies, to contrast with his monstrous appearance. His struggle with his animal side is a noble and courageous one, especially as he does it solely to protect Belle from himself.

Fig. 2. Belle still.

One could argue that the Beast’s transformation into a handsome prince ‘removes an essential element from the Beast’ (Cannon, 1997). What made the story so charming was Belle’s love of the monster – transforming him back as a ‘reward’ seems to cheapen Belle’s love. While it is clearly stating that kindness will be rewarded, giving Belle a handsome lover as a reward when the film went to great pains to show that physical attractiveness did not matter seems somewhat hypocritical.

Made in the wake of World War II, the film provided France something it desperately needed – ‘pure escapism, blessed relief from the painful memories of the Occupation and the penury of post-war austerity’ (Travers, 2001). The film is visually surreal, with actors incorporated into furniture, candlelight carefully thrown onto billowing curtains and a conscious and bizarre interplay of light and shadow. The film’s being in black-and-white serves it well, as colour would only interfere with the contrasts between light and dark. However, ultimately the film does not rely ‘on astonishing special effects but on the private thoughts of the watcher’ (Malcolm, 1999) to make its impact – the visuals serve only to transport the viewer into the magical world of the Beast’s castle, rather than act as the be-all and end-all of the film.

Fig. 3. Candelabra still.

Illustration List

Figure 1. Cocteau, Jean. (1946) Belle and the Beast still. At: http://stuartfernie.org/belleetbete4.jpg (Accessed on 27/09/11)

Figure 2. Cocteau, Jean. (1946) Belle still. At: http://wondersinthedark.files.wordpress.com/2008/12/belle-et-la-bete-1-copy.jpg?w=500&h=375 (Accessed on 27/09/11)

Figure 3. Cocteau, Jean. (1946) Candelabra still. At: https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-V2LwuebYrPZ3dLJa8y-bVCy5hB0Tf4V5oKC8pf_foR5pFKAYTIioaWTqedqEb5_58vKCWprpu-1XEM5VpKJ7dNkkYUFVw0zy3-7Jnj06Bwq2HrOMrIjg-ClWPSSsZR3ps14hINpfFiw/s1600/La+belle+et+la+bete+film+stills.jpeg (Accessed on 27/09/11)

Bibliography

Cannon, D. (1997) Movie Reviews UK. http://www.film.u-net.com/Movies/Reviews/Belle_Bete.html (Accessed on 27/09/11)

Travers, J. (2000) Films de France. http://filmsdefrance.com/FDF_La_belle_et_la_bete_rev.html (Accessed on 27/09/11)

Malcolm, D. (1999) The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/1999/jul/01/1 (Accessed on 27/09/11)

Wednesday 21 September 2011

Life Drawing & Hand Studies

Apologies for the dreadful image quality, I am still trying to wrangle my camera into submission and clearly my Photoshop-fu is too weak to actually get photos to cooperate.

The first drawing of the class, which is pretty bad. My life drawing is rather rusty - haven't drawn from life in about a year - and I tend to need to do one or two dreadful drawings at the beginning of a drawing session before I can work properly. I don't resent this, it's just how I work. I'd have appreciated it if we could have worked a bit faster so I could have some more decent drawings, but it's not a problem.

As can be seen, I am infinitely better at drawing nude figures than clothed ones. I have never done clothed life drawing before, so this one is naturally better. Clothes tend to confuse me - my eyes trip over the folds as I try to move my eye around the figure - so my nude drawings tend to come out more successfully. Still a bit wonky, especially around the feet and shoulders, though.

Last drawing of the night, again with a clothed model (hi Sammy!). This one is far better than my first shot, particularly around the face and shoulders. The limbs confused me, so she looks more suited to be QWOPing rather than the austere monument her face suggests she should be. Ah well.

The centre one of these (the 'begging' gesture with the thumb towards the viewer) is my favourite of these studies. I always find being gentle with my work yields the best results, yet I'm often too impatient to be gentle. Definitely something to work on. The others aren't dreadful, but still somewhat clunky.

The top one of these isn't bad bar the wonky foreshortening on the thumb - what made me think that pose was a good idea? The bottom one is my other favourite;

The first drawing of the class, which is pretty bad. My life drawing is rather rusty - haven't drawn from life in about a year - and I tend to need to do one or two dreadful drawings at the beginning of a drawing session before I can work properly. I don't resent this, it's just how I work. I'd have appreciated it if we could have worked a bit faster so I could have some more decent drawings, but it's not a problem.

As can be seen, I am infinitely better at drawing nude figures than clothed ones. I have never done clothed life drawing before, so this one is naturally better. Clothes tend to confuse me - my eyes trip over the folds as I try to move my eye around the figure - so my nude drawings tend to come out more successfully. Still a bit wonky, especially around the feet and shoulders, though.

Last drawing of the night, again with a clothed model (hi Sammy!). This one is far better than my first shot, particularly around the face and shoulders. The limbs confused me, so she looks more suited to be QWOPing rather than the austere monument her face suggests she should be. Ah well.

The centre one of these (the 'begging' gesture with the thumb towards the viewer) is my favourite of these studies. I always find being gentle with my work yields the best results, yet I'm often too impatient to be gentle. Definitely something to work on. The others aren't dreadful, but still somewhat clunky.

The top one of these isn't bad bar the wonky foreshortening on the thumb - what made me think that pose was a good idea? The bottom one is my other favourite;

David Cronenberg's 'The Fly' (1986)

Fig. 1 The Fly poster

David Cronenberg’s 1986 remake of The Fly is greatly different from the original in terms of storytelling and context, even though the general premise and themes are the same. Cronenberg updates the story, placing it in a contemporary setting with contemporary issues, using the lead character Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum)’s painful, cancerous metamorphosis into the ‘Brundle-fly’ as a clear metaphor for HIV/AIDS, which had only recently emerged and was in the forefront of the public mind. In the premise of The Fly, Cronenberg ‘saw not only a perfect vehicle for his own peculiar brand of body horror but also for a thoughtful meditation on coping with malignant illness and loss’ (Sommerlad, 2009).

Furthermore, the movie discusses female rights to abortion, as the secondary protagonist Veronica Quaife (Geena Davis) is very clear that due to the likelihood of Brundle’s child being another human-fly hybrid she wants it aborted. The use of the phrase ‘I want it out of my body’ particularly touches upon this, as it echoes a major pro-abortion argument; that it is a person’s right to decide what goes on in their body. In addition to this it looks at the ethics of bearing a deformed or disabled child; while the metaphor used is wild and improbable, the underlying themes are relevant even today.

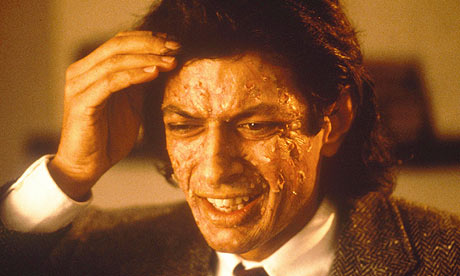

Rather than a clean theriocephalic hybridisation as in the Kurt Neumann version of the film, Cronenberg instead makes Brundle’s transformation slow and agonising as his very body turns against him (another HIV reference). As well as being utterly vile to watch, this highlights the characters’ humanity even further; Quaife hugs Brundle even after he vomits acid onto food to digest it and loses his ear. It is arguably more poignant than the original as Quaife refuses to abandon Brundle even as she sees firsthand how he becomes a monster. ‘What remains of Seth the scientist is all too aware of the monster he is turning into: an efficient killer with "no compassion, no compromise."’ (Corliss, 1986), making the transformation even more dreadful.

The special effects and make-up have clearly come forward in leaps and bounds from the rubber mask days of the original, creating a gruesome monstrosity (The Fly won an Oscar for Best Make-up). It could be argued that this makes what is a beautiful story difficult to access, though on the other hand the body horror element is what makes the story so powerful. It has, however, been argued that the film tries too hard; ‘this all-out, flaunted goriness becomes distracting, and it destroys ''The Fly,'' which is too bad, because Mr. Goldblum's fly-man has heart and humor, and Mr. Cronenberg's vision is ambitious.’ (James, 1986). Ultimately the themes of the two movies are the same; devotion and love for a human being even as he degenerates into a monster.

List of Illustrations

Figure 1. Cronenberg, David (1986) The Fly Poster. At: http://images.wikia.com/horrormovies/images/7/76/Fly_poster-1-.jpg (Accessed on 04/10/11)

Figure 2. Cronenberg, David (1986) Brundle still. At: https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEinBpjxVPWwexgQp4h84tWzpv3VyYLcwvLoD4nibm3zedMUAZMH-FtgjAnuDstyNPqS3i7msYW5bbl78XoEFWfiDovv2jsp1pEdSD-uew6Lg91ILVtPEDIstelg0hTcXQjFhLwCAaecdaA/s400/fly_1986_xl_01--film-A.jpg (Accessed on 04/10/11)

Figure 2. Cronenberg, David (1986) Brundle mid-transformation still. At: http://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Film/Pix/pictures/2009/9/25/1253884210077/Jeff-Goldblum-in-The-Fly--001.jpg (Accessed on 04/10/11)

Figure 4. Cronenberg, David (1986) Brundlefly still. At: http://cdn.jamesgunn.com/wp-content/uploads/fly_1_remake.jpg?81196f (Accessed on 04/10/11)

Figure 2. Cronenberg, David (1986) Brundle still. At: https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEinBpjxVPWwexgQp4h84tWzpv3VyYLcwvLoD4nibm3zedMUAZMH-FtgjAnuDstyNPqS3i7msYW5bbl78XoEFWfiDovv2jsp1pEdSD-uew6Lg91ILVtPEDIstelg0hTcXQjFhLwCAaecdaA/s400/fly_1986_xl_01--film-A.jpg (Accessed on 04/10/11)

Figure 2. Cronenberg, David (1986) Brundle mid-transformation still. At: http://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Film/Pix/pictures/2009/9/25/1253884210077/Jeff-Goldblum-in-The-Fly--001.jpg (Accessed on 04/10/11)

Figure 4. Cronenberg, David (1986) Brundlefly still. At: http://cdn.jamesgunn.com/wp-content/uploads/fly_1_remake.jpg?81196f (Accessed on 04/10/11)

Bibliography

Sommerlad, J. (2009) Celluloid Dreams. http://www.celluloiddreams.co.uk/thefly.html (Accessed on 21/09/11)

Corliss, R. (1986) Love in the Animal Kingdom the Fly In: Time Magazine. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,962069-1,00.html (Accessed on 21/09/11)

James, C. (1986) ‘The Fly’ with Jeff Goldblum In: The New York Times. http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9A0DE0D71438F936A2575BC0A960948260 (Accessed on 21/09/11)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)